Lucid Simple

Binary Fixtures with Wireshark

TL;DR - if you are new to Elixir and are anxious to write something that is not a web application, then some basic knowledge of a packet analyzer along with binary parsing and unit testing will help greatly.

If you’re not currently trying to parse a binary protocol (e.g writing your own Redis client or DNS server), then this week’s post probably won’t be valuable to you.

Overview

Elixir has some amazing tools for web development, but lately I’ve been trying to stretch out of my normal comfort zone of responding to HTTP requests, querying databases, and spitting strings back at browsers.

One skill that I’ve been exercising lately is parsing binary streams and files. In particular, I’ve been trying to understand DNS a little bit better and get a better feel for what is happening over the wire.

There are several RFCs for DNS, but the two most important ones are RFCs 1034 and 1035. The RFCs are the official spec, but if you’ve been spoiled by IEx and IRB, you may struggle a little bit until you get something more interactive. Enter Wireshark.

Wireshark

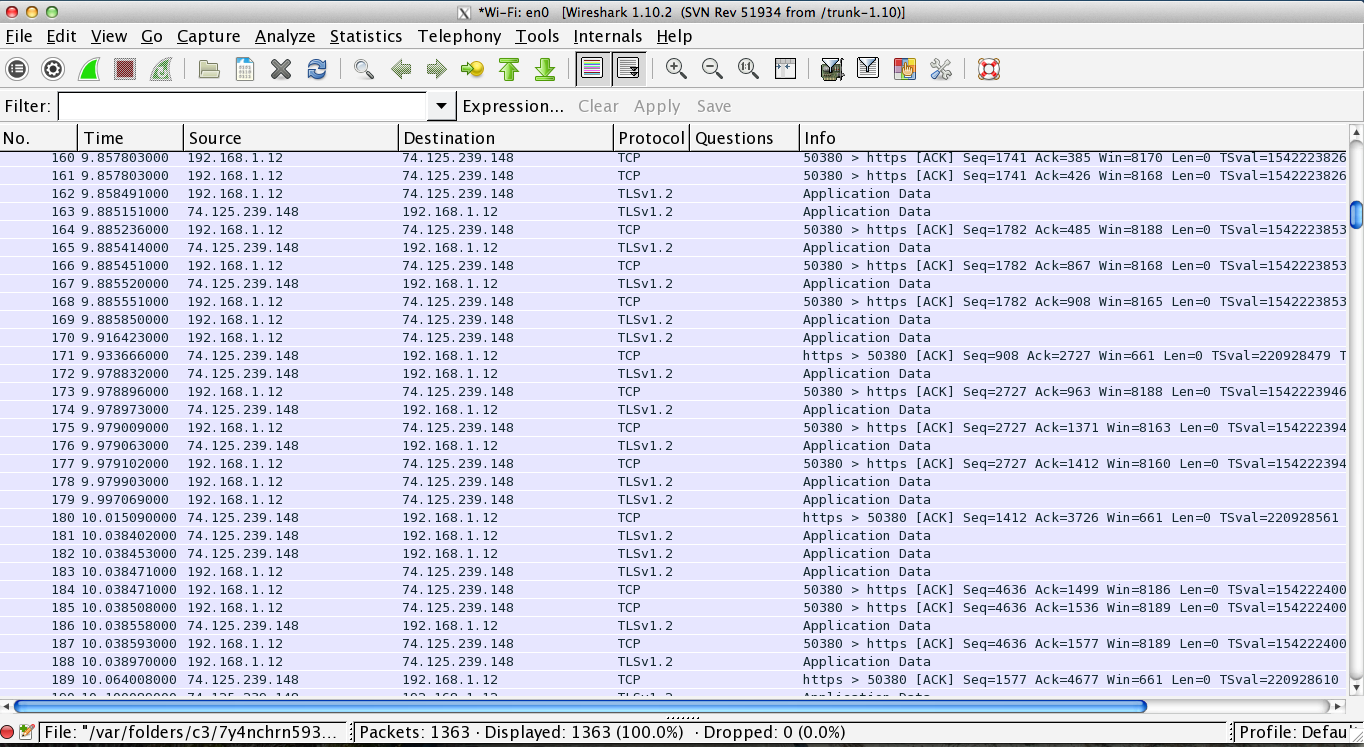

Wireshark is a pretty bad ass packet analyzer. After launching and selecting the interface or interfaces you want to listen on, Wireshark will render all the the packets as it sees them.

If you select an interface with a lot of activity on it, be prepared for a veritable shit storm of data. Click on the screenshot to get a closer look.

My gut feeling is that most people playing with a packet sniffer end up seeing something like the screenshot above, find it unusable, and never open it up again.

Thankfully we can be a bit more selective about what we want.

Homing in on relevant data

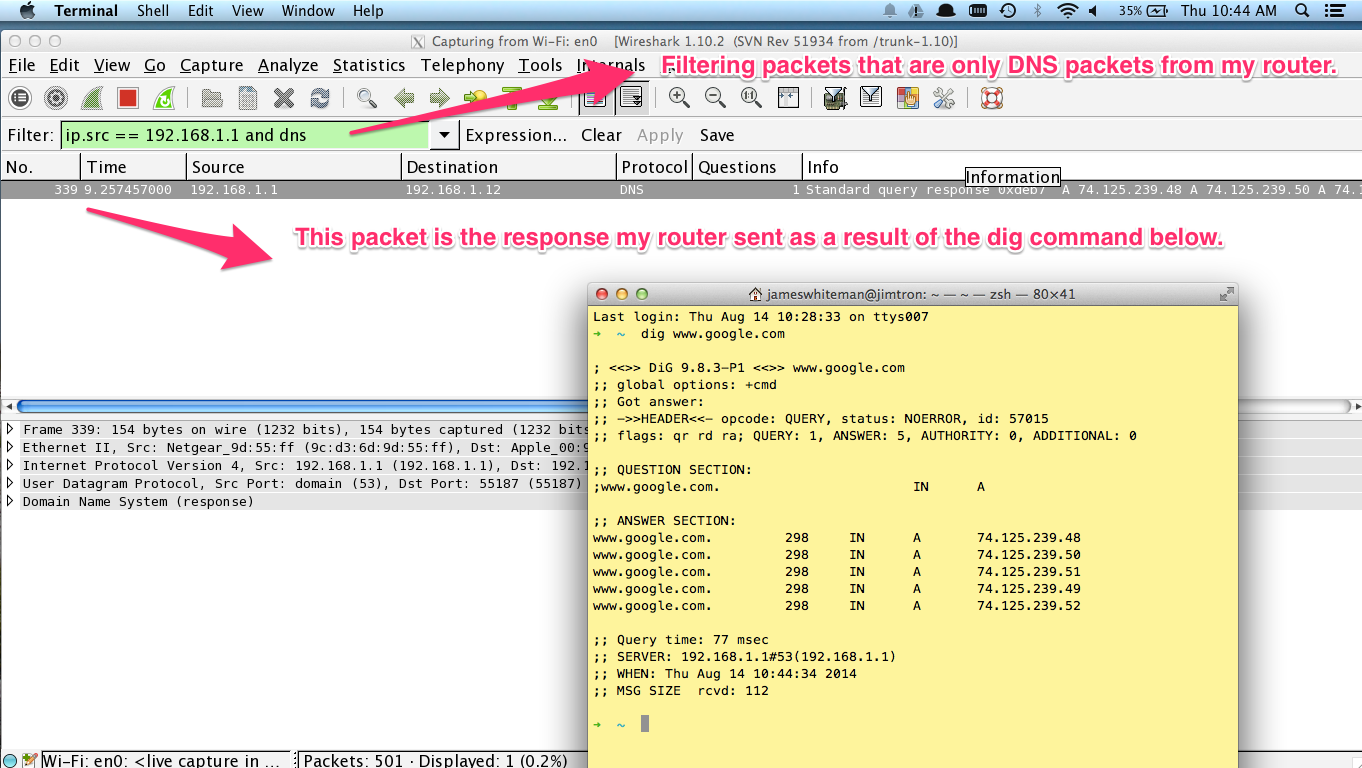

In this tutorial I’m wanting to learn more about DNS. More specifically, I want to know what a typical DNS response looks like from my router.

But currently, the amount of information noise makes it impossible to analyze anything.

It would be helpful to filter only DNS packets that come specifically from my router’s IP.

So let’s do that. Click on the screenshot to see more detail.

The filter logic is easy enough to read: ip.src == 192.168.1.1 and dns.

After the filter is applied my 1300+ packets whittled down to a single packet that

came from the dig command I ran in the terminal querying www.google.com.

Digging into a packet

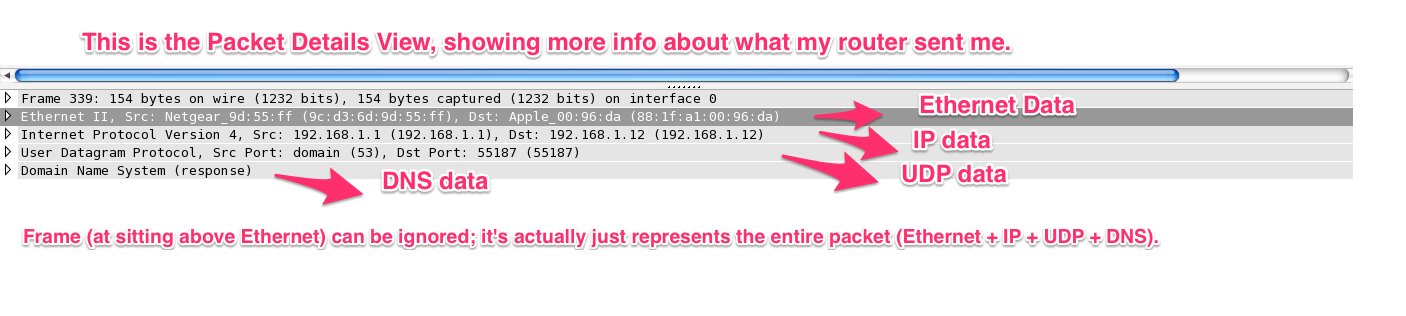

If we concentrate for a moment on the lowest pane from the screenshot above, we can see that Wireshark has divied up the data into 4 parts: Ethernet Data, IP data, UDP data, and DNS data.

Click the image to zoom in.

It looks like there are actually 5 parts, but “Frame” simply represents the whole response, from start to finish.

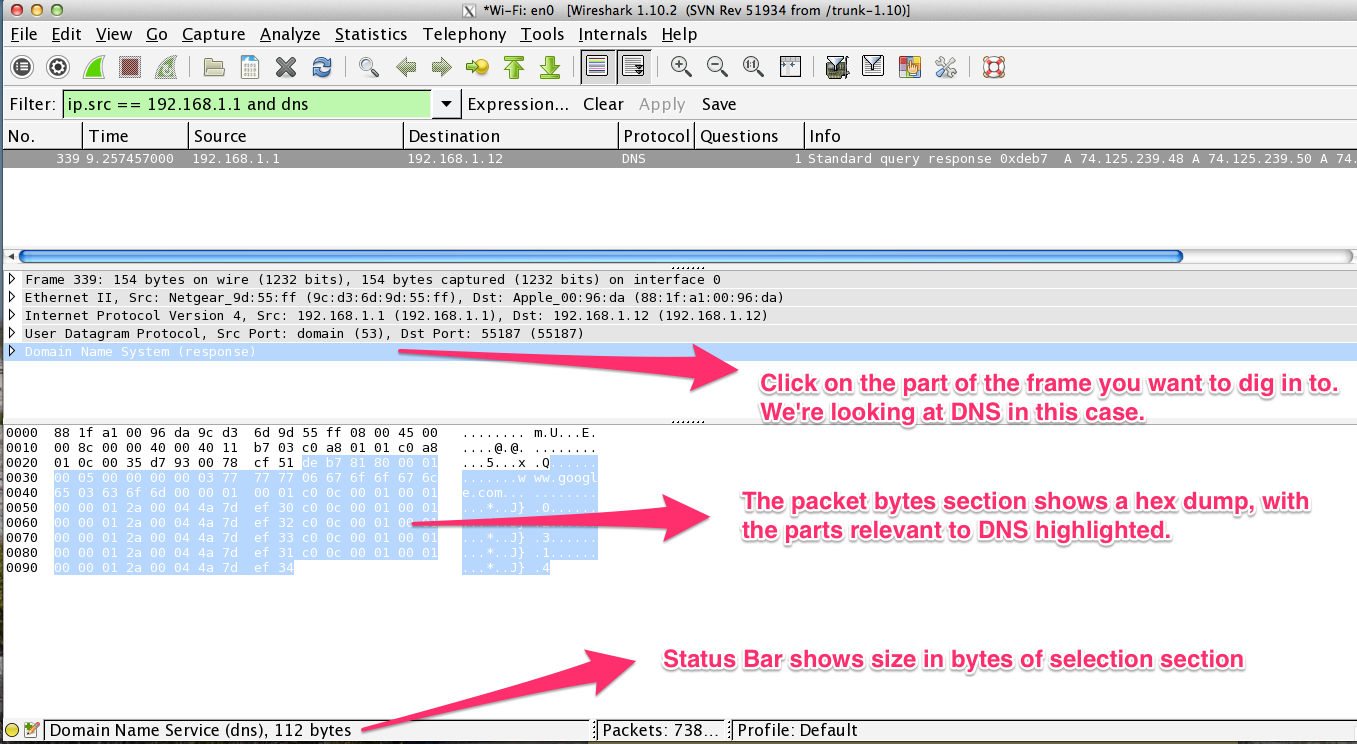

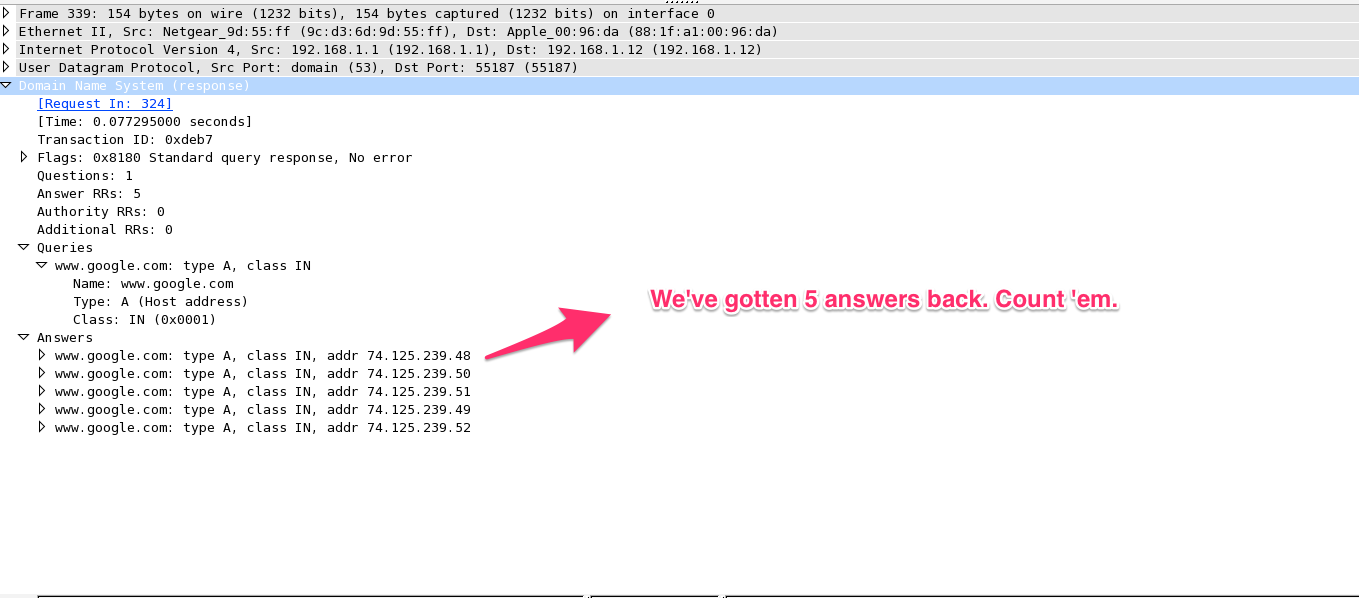

Clicking on the section you’re interested in (DNS in this case), yields even more information:

In this case, we get to see a hex dump of DNS response, separated out from the Ethernet, IP & UDP data. Nice.

Creating a Fixture

We’ve got our hands on some binary data that we know is legit. We could have used the RFC to craft a response, but getting our hands on a real response in-the-wild that we can use as a fixture is very useful.

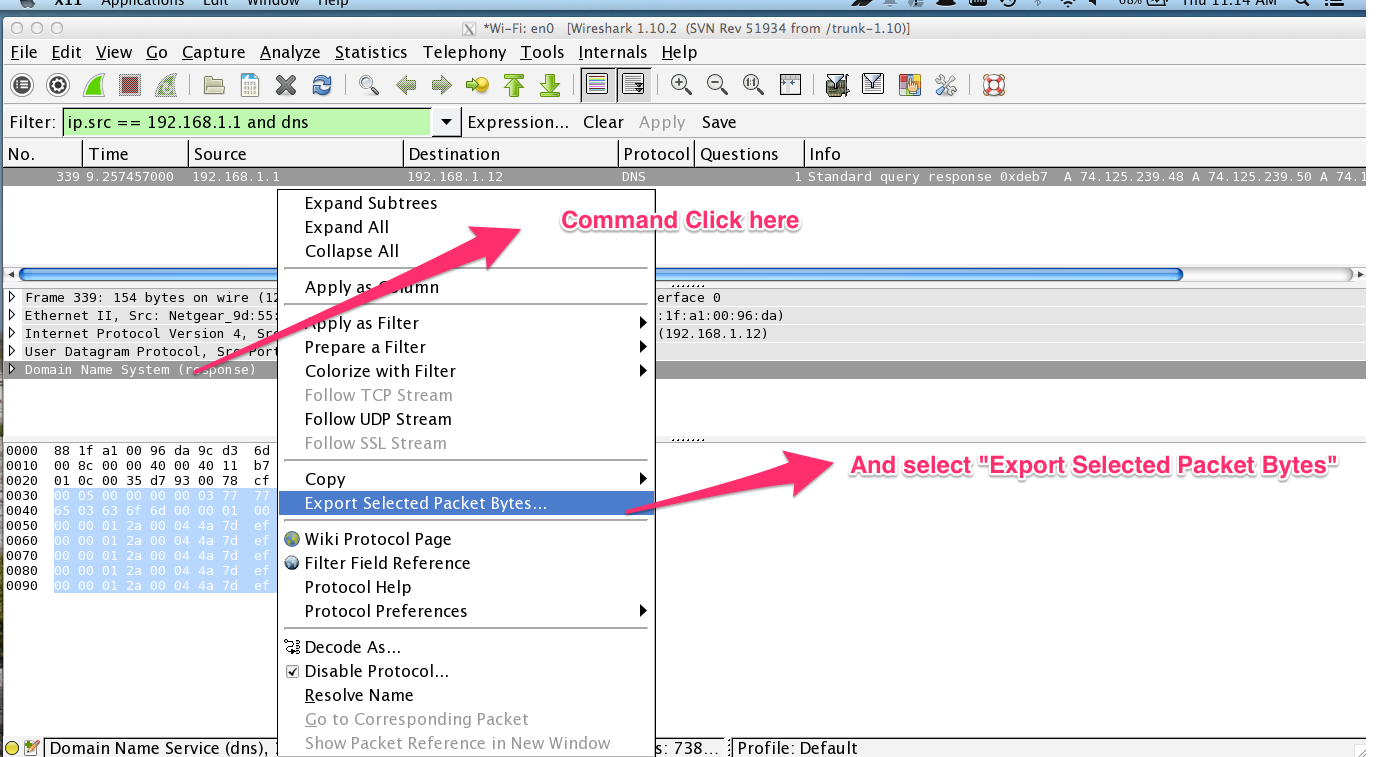

Saving the DNS data as a binary is simple. Command click (mac) “Domain Name System” in the packet details pane and select “Export Selected Packet Bytes”.

You’ll be able to save the binary to a file that you can pull in as a fixture in your tests.

Note: if Command Click doesn’t work, you’ll need to enable it in the options.

Example: Using the Fixture

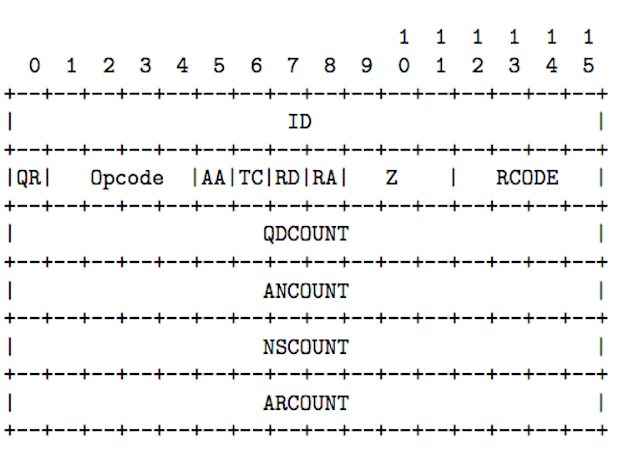

How might we use this? Let’s take a quick look at what the response header is supposed to look like:

We’ve got a 16 bit ID, followed by 16 bits of configuration, followed by 16 bits representing the number of questions (one question: www.google.com), followed by 16 bits representing the number of answers followed by 32 bits of the NSCOUNT and ARCOUNT, respectively.

As a challange let’s try to parse the number of answers that this binary has in its header.

Let’s open up an interactive Elixir session in the terminal with iex.

Assume that the binary exported is in a file named ‘dns-response.bin’.

{:ok,

<<id::size(16), # Match the first 16 bits against _Id

details::size(16), # Match the next 16 bits against _Details

nq::size(16), # Match the next 16 bits against _NQ

num_answers::size(16), # This is the value we are interested in.

_rest::binary>> # The rest of the bits

} = File.read('dns-response.bin')

5 = num_answers

# => 5I won’t dig into binary parsing with Elixir, but the example should be readable.

Evaluating num_answsers gives us 5.

Is that the correct number? Let’s go back to the packet in Wireshark. Click the image to get a better view.

Looks like we got it correct. Elixir bit syntax & Wireshark make it easy to get things right.

Final Thoughts.

Using a fixture like this would make it easier to write tests. If you’re writing a DNS server and you’re not particularly knowledgable of DNS then this approach would be quite valuable.

That’s not to say that the RFCs are not useful. I believe they are. But in the real world, servers don’t always conform to the spec. For example, DNS headers have a section called QDCOUNT.

In theory, QDCOUNT could be any natural number. In practice it’s always one.

I am still figuring out what works best for me, but for now, a combination of the spec and poking things with Wireshark is the best combination.

This is allowing me to write a different class of applications that I previously wasn’t able to - which is precisely why I wanted to learn Elixir in the first place.

– Jim